Microsoft processes 24 trillion signals every 24 hours, and we have blocked billions of attacks in the last year alone. Microsoft Security tracks more than 35 unique ransomware families and 250 unique threat actors across observed nation-state, ransomware, and criminal activities.

That depth of signal intelligence gathered from various domains—identity, email, data, and cloud—provides us with insight into the gig economy that attackers have created with tools designed to lower the barrier for entry for other attackers, who in turn continue to pay dividends and fund operations through the sale and associated “cut” from their tool’s success.

The cybercriminal economy is a continuously evolving connected ecosystem of many players with different techniques, goals, and skillsets. In the same way our traditional economy has shifted toward gig workers for efficiency, criminals are learning that there’s less work and less risk involved by renting or selling their tools for a portion of the profits than performing the attacks themselves. This industrialization of the cybercrime economy has made it easier for attackers to use ready-made penetration testing and other tools to perform their attacks.

Within this category of threats, Microsoft has been tracking the trend in the ransomware as a service (RaaS) gig economy, called human-operated ransomware, which remains one of the most impactful threats to organizations. We coined the industry term “human-operated ransomware” to clarify that these threats are driven by humans who make decisions at every stage of their attacks based on what they find in their target’s network.

Unlike the broad targeting and opportunistic approach of earlier ransomware infections, attackers behind these human-operated campaigns vary their attack patterns depending on their discoveries—for example, a security product that isn‘t configured to prevent tampering or a service that’s running as a highly privileged account like a domain admin. Attackers can use those weaknesses to elevate their privileges to steal even more valuable data, leading to a bigger payout for them—with no guarantee they’ll leave their target environment once they’ve been paid. Attackers are also often more determined to stay on a network once they gain access and sometimes repeatedly monetize that access with additional attacks using different malware or ransomware payloads if they aren’t successfully evicted.

Ransomware attacks have become even more impactful in recent years as more ransomware as a service ecosystems have adopted the double extortion monetization strategy. All ransomware is a form of extortion, but now, attackers are not only encrypting data on compromised devices but also exfiltrating it and then posting or threatening to post it publicly to pressure the targets into paying the ransom. Most ransomware attackers opportunistically deploy ransomware to whatever network they get access to, and some even purchase access to networks from other cybercriminals. Some attackers prioritize organizations with higher revenues, while others prefer specific industries for the shock value or type of data they can exfiltrate.

All human-operated ransomware campaigns—all human-operated attacks in general, for that matter—share common dependencies on security weaknesses that allow them to succeed. Attackers most commonly take advantage of an organization’s poor credential hygiene and legacy configurations or misconfigurations to find easy entry and privilege escalation points in an environment.

In this blog, we detail several of the ransomware ecosystems using the RaaS model, the importance of cross-domain visibility in finding and evicting these actors, and best practices organizations can use to protect themselves from this increasingly popular style of attack. We also offer security best practices on credential hygiene and cloud hardening, how to address security blind spots, harden internet-facing assets to understand your perimeter, and more. Here’s a quick table of contents:

1. How RaaS redefines our understanding of ransomware incidents

With ransomware being the preferred method for many cybercriminals to monetize attacks, human-operated ransomware remains one of the most impactful threats to organizations today, and it only continues to evolve. This evolution is driven by the “human-operated” aspect of these attacks—attackers make informed and calculated decisions, resulting in varied attack patterns tailored specifically to their targets and iterated upon until the attackers are successful or evicted.

In the past, we’ve observed a tight relationship between the initial entry vector, tools, and ransomware payload choices in each campaign of one strain of ransomware. The RaaS affiliate model, which has allowed more criminals, regardless of technical expertise, to deploy ransomware built or managed by someone else, is weakening this link. As ransomware deployment becomes a gig economy, it has become more difficult to link the tradecraft used in a specific attack to the ransomware payload developers.

Reporting a ransomware incident by assigning it with the payload name gives the impression that a monolithic entity is behind all attacks using the same ransomware payload and that all incidents that use the ransomware share common techniques and infrastructure. However, focusing solely on the ransomware stage obscures many stages of the attack that come before, including actions like data exfiltration and additional persistence mechanisms, as well as the numerous detection and protection opportunities for network defenders.

We know, for example, that the underlying techniques used in human-operated ransomware campaigns haven’t changed very much over the years—attacks still prey on the same security misconfigurations to succeed. Securing a large corporate network takes disciplined and sustained focus, but there’s a high ROI in implementing critical controls that prevent these attacks from having a wider impact, even if it’s only possible on the most critical assets and segments of the network.

Without the ability to steal access to highly privileged accounts, attackers can’t move laterally, spread ransomware widely, access data to exfiltrate, or use tools like Group Policy to impact security settings. Disrupting common attack patterns by applying security controls also reduces alert fatigue in security SOCs by stopping the attackers before they get in. This can also prevent unexpected consequences of short-lived breaches, such as exfiltration of network topologies and configuration data that happens in the first few minutes of execution of some trojans.

In the following sections, we explain the RaaS affiliate model and disambiguate between the attacker tools and the various threat actors at play during a security incident. Gaining this clarity helps surface trends and common attack patterns that inform defensive strategies focused on preventing attacks rather than detecting ransomware payloads. Threat intelligence and insights from this research also enrich our solutions like Microsoft 365 Defender, whose comprehensive security capabilities help protect customers by detecting RaaS-related attack attempts.

The RaaS affiliate model explained

The cybercriminal economy—a connected ecosystem of many players with different techniques, goals, and skillsets—is evolving. The industrialization of attacks has progressed from attackers using off-the-shelf tools, such as Cobalt Strike, to attackers being able to purchase access to networks and the payloads they deploy to them. This means that the impact of a successful ransomware and extortion attack remains the same regardless of the attacker’s skills.

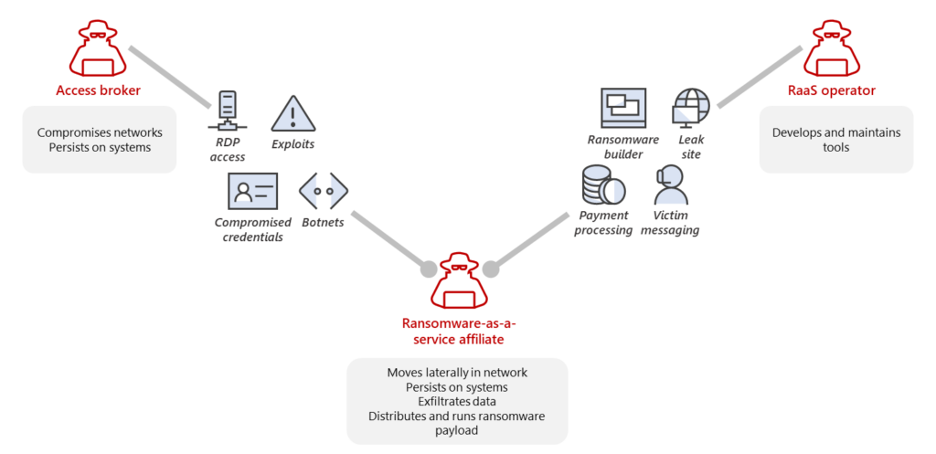

RaaS is an arrangement between an operator and an affiliate. The RaaS operator develops and maintains the tools to power the ransomware operations, including the builders that produce the ransomware payloads and payment portals for communicating with victims. The RaaS program may also include a leak site to share snippets of data exfiltrated from victims, allowing attackers to show that the exfiltration is real and try to extort payment. Many RaaS programs further incorporate a suite of extortion support offerings, including leak site hosting and integration into ransom notes, as well as decryption negotiation, payment pressure, and cryptocurrency transaction services

RaaS thus gives a unified appearance of the payload or campaign being a single ransomware family or set of attackers. However, what happens is that the RaaS operator sells access to the ransom payload and decryptor to an affiliate, who performs the intrusion and privilege escalation and who is responsible for the deployment of the actual ransomware payload. The parties then split the profit. In addition, RaaS developers and operators might also use the payload for profit, sell it, and run their campaigns with other ransomware payloads—further muddying the waters when it comes to tracking the criminals behind these actions.

Access for sale and mercurial targeting

A component of the cybercriminal economy is selling access to systems to other attackers for various purposes, including ransomware. Access brokers can, for instance, infect systems with malware or a botnet and then sell them as a “load”. A load is designed to install other malware or backdoors onto the infected systems for other criminals. Other access brokers scan the internet for vulnerable systems, like exposed Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) systems with weak passwords or unpatched systems, and then compromise them en masse to “bank” for later profit. Some advertisements for the sale of initial access specifically cite that a system isn’t managed by an antivirus or endpoint detection and response (EDR) product and has a highly privileged credential such as Domain Administrator associated with it to fetch higher prices.

Most ransomware attackers opportunistically deploy ransomware to whatever network they get access to. Some attackers prioritize organizations with higher revenues, while some target specific industries for the shock value or type of data they can exfiltrate (for example, attackers targeting hospitals or exfiltrating data from technology companies). In many cases, the targeting doesn’t manifest itself as specifically attacking the target’s network, instead, the purchase of access from an access broker or the use of existing malware infection to pivot to ransomware activities.

In some ransomware attacks, the affiliates who bought a load or access may not even know or care how the system was compromised in the first place and are just using it as a “jump server” to perform other actions in a network. Access brokers often list the network details for the access they are selling, but affiliates aren’t usually interested in the network itself but rather the monetization potential. As a result, some attacks that seem targeted to a specific industry might simply be a case of affiliates purchasing access based on the number of systems they could deploy ransomware to and the perceived potential for profit.

Microsoft coined the term “human-operated ransomware” to clearly define a class of attacks driven by expert human intelligence at every step of the attack chain and culminate in intentional business disruption and extortion. Human-operated ransomware attacks share commonalities in the security misconfigurations of which they take advantage and the manual techniques used for lateral movement and persistence. However, the human-operated nature of these actions means that variations in attacks—including objectives and pre-ransom activity—evolve depending on the environment and the unique opportunities identified by the attackers.

These attacks involve many reconnaissance activities that enable human operators to profile the organization and know what next steps to take based on specific knowledge of the target. Many of the initial access campaigns that provide access to RaaS affiliates perform automated reconnaissance and exfiltration of information collected in the first few minutes of an attack.

After the attack shifts to a hands-on-keyboard phase, the reconnaissance and activities based on this knowledge can vary, depending on the tools that come with the RaaS and the operator’s skill. Frequently attackers query for the currently running security tools, privileged users, and security settings such as those defined in Group Policy before continuing their attack. The data discovered via this reconnaissance phase informs the attacker’s next steps.

If there’s minimal security hardening to complicate the attack and a highly privileged account can be gained immediately, attackers move directly to deploying ransomware by editing a Group Policy. The attackers take note of security products in the environment and attempt to tamper with and disable these, sometimes using scripts or tools provided with RaaS purchase that try to disable multiple security products at once, other times using specific commands or techniques performed by the attacker.

This human decision-making early in the reconnaissance and intrusion stages means that even if a target’s security solutions detect specific techniques of an attack, the attackers may not get fully evicted from the network and can use other collected knowledge to attempt to continue the attack in ways that bypass security controls. In many instances, attackers test their attacks “in production” from an undetected location in their target’s environment, deploying tools or payloads like commodity malware. If these tools or payloads are detected and blocked by an antivirus product, the attackers simply grab a different tool, modify their payload, or tamper with the security products they encounter. Such detections could give SOCs a false sense of security that their existing solutions are working. However, these could merely serve as a smokescreen to allow the attackers to further tailor an attack chain that has a higher probability of success. Thus, when the attack reaches the active attack stage of deleting backups or shadow copies, the attack would be minutes away from ransomware deployment. The adversary would likely have already performed harmful actions like the exfiltration of data. This knowledge is key for SOCs responding to ransomware: prioritizing investigation of alerts or detections of tools like Cobalt Strike and performing swift remediation actions and incident response (IR) procedures are critical for containing a human adversary before the ransomware deployment stage.

Exfiltration and double extortion

Ransomware attackers often profit simply by disabling access to critical systems and causing system downtime. Although that simple technique often motivates victims to pay, it is not the only way attackers can monetize their access to compromised networks. Exfiltration of data and “double extortion,” which refers to attackers threatening to leak data if a ransom hasn’t been paid, has also become a common tactic among many RaaS affiliate programs—many of them offering a unified leak site for their affiliates. Attackers take advantage of common weaknesses to exfiltrate data and demand ransom without deploying a payload.

This trend means that focusing on protecting against ransomware payloads via security products or encryption, or considering backups as the main defense against ransomware, instead of comprehensive hardening, leaves a network vulnerable to all the stages of a human-operated ransomware attack that occur before ransomware deployment. This exfiltration can take the form of using tools like Rclone to sync to an external site, setting up email transport rules, or uploading files to cloud services. With double extortion, attackers don’t need to deploy ransomware and cause downtime to extort money. Some attackers have moved beyond the need to deploy ransomware payloads and are shifting straight to extortion models or performing the destructive objectives of their attacks by directly deleting cloud resources. One such extortion attackers is DEV-0537 (also known as LAPSUS$), which is profiled below.

Persistent and sneaky access methods

Paying the ransom may not reduce the risk to an affected network and potentially only serves to fund cybercriminals. Giving in to the attackers’ demands doesn’t guarantee that attackers ever “pack their bags” and leave a network. Attackers are more determined to stay on a network once they gain access and sometimes repeatedly monetize attacks using different malware or ransomware payloads if they aren’t successfully evicted.

The handoff between different attackers as transitions in the cybercriminal economy occur means that multiple attackers may retain persistence in a compromised environment using an entirely different set of tools from those used in a ransomware attack. For example, initial access gained by a banking trojan leads to a Cobalt Strike deployment, but the RaaS affiliate that purchased the access may choose to use a less detectable remote access tool such as TeamViewer to maintain persistence on the network to operate their broader series of campaigns. Using legitimate tools and settings to persist versus malware implants such as Cobalt Strike is a popular technique among ransomware attackers to avoid detection and remain resident in a network for longer.

Some of the common enterprise tools and techniques for persistence that Microsoft has observed being used include:

Another popular technique attackers perform once they attain privilege access is the creation of new backdoor user accounts, whether local or in Active Directory. These newly created accounts can then be added to remote access tools such as a virtual private network (VPN) or Remote Desktop, granting remote access through accounts that appear legitimate on the network. Ransomware attackers have also been observed editing the settings on systems to enable Remote Desktop, reduce the protocol’s security, and add new users to the Remote Desktop Users group.

The time between initial access to a hands-on keyboard deployment can vary wildly depending on the groups and their workloads or motivations. Some activity groups can access thousands of potential targets and work through these as their staffing allows, prioritizing based on potential ransom payment over several months. While some activity groups may have access to large and highly resourced companies, they prefer to attack smaller companies for less overall ransom because they can execute the attack within hours or days. In addition, the return on investment is higher from companies that can’t respond to a major incident. Ransoms of tens of millions of dollars receive much attention but take much longer to develop. Many groups prefer to ransom five to 10 smaller targets in a month because the success rate at receiving payment is higher in these targets. Smaller organizations that can’t afford an IR team are often more likely to pay tens of thousands of dollars in ransom than an organization worth millions of dollars because the latter has a developed IR capability and is likely to follow legal advice against paying. In some instances, a ransomware associate threat actor may have an implant on a network and never convert it to ransom activity. In other cases, initial access to full ransom (including handoff from an access broker to a RaaS affiliate) takes less than an hour.

The human-driven nature of these attacks and the scale of possible victims under control of ransomware-associated threat actors underscores the need to take targeted proactive security measures to harden networks and prevent these attacks in their early stages.

Contact us to speak with an expert from LogixCare on best practices you can use to protect your organization from this increasingly popular style of attack.

Phone: (305) 517 1000

Support: (305) 517 1001

Email: [email protected]

LogixCare LLC. 2023 © All Rights Reserved